TOOLS OF REPRESENTATION

The most difficult and most important task is to truly see sites, to understand their size and nature. In order to transform them, one must possess a true command of their scale. I believe that in our profession, and in architecture in general, the relevance given to scale in the response of a project is of most importance. Not so much skill, as the relevance of scale. Understanding exactly where one is, in order to effectively act there.

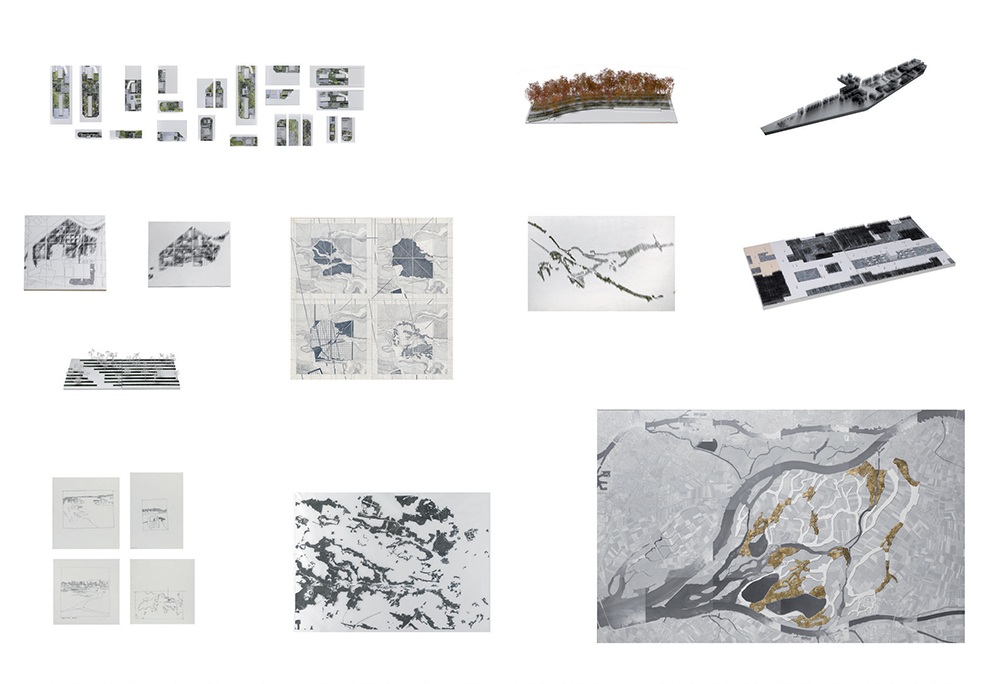

For this to be possible we need to make use of several tools - designs, models, collages, photographs - and perhaps at each step of the way the tool at our disposal needs to be reinvented, allowing us to distance ourselves from the tool employed previously.

However just as these tools are useful, they are also traps, each containing the potential of enclosing us within the pleasure of its representation, stuck in a simulacrum. And there is really no ultimate escape from this pleasure of representation, from the specific autonomy representation acquires. No one escapes from its attraction, except through the continual alternation of means, each step of the way inventing or reinventing the means that will succeed in breaking with the preceding, a process that continues until the project has taken definitive shape, and returns to the site itself. For all that, we need these tools.

I do not believe that merely being on site, with physical means at our disposal, is sufficient for taking action on sites. Reality is too complex, oftentimes too large, to allow for a conception of what makes it up without the help of models or images.

Freeing oneself from the real becomes necessary in conceiving something in regards to it, and thus in acting upon it. But we must continue mistrusting and questioning the instruments, images, representations that make this possible. They serve in the realization of our designs, but after using them we should immediately replace them with the next, so as to achieve the correct scale in our projects and enable us to lose our fascination for the instrument, for the medium.

LANDSCAPES IN COUNTERPOINT

It takes a long time to persuade a group or community to commit to a project. At times the project in the end comes to be defined very quickly, in urgency, always in urgency. There is thus a terrible paradox between long periods of gestation and an extremely quick formulation, which nonetheless does not pain me at all. I believe rather that this situation allows us to remain relevant, to dispense with all the connotations that can accumulate precisely during these long years of conception. Renzo Piano speaks in essence very positively of this, as have others before him. I believe that in order to succeed in creating something, a certain detachment is necessary.

Yes, a certain belief, ability, as well as detachment is necessary. And attaining detachment does not go without saying. The unexpected emergency, oftentimes feared, places us in a detached position where we are compelled to create with a certain vigor.

SPATIAL COMPOSITION

I belong to a generation that considered spatial composition taboo. This was also true of architects, as well as of certain visual artists who would allude rather to an interplay of textures, but rarely to composition, geometrical or otherwise.

But it is clear that we cannot simply dispense with manifest spatial organization. A moment comes when a boundary is reached. If there is a clearing, there is a place where it ends and where something else begins. What is the form of this clearing? What are its proportions?

Perhaps we should look back anew at certain 19th century experiments that went unexamined, ignored, were considered taboo in the past. Often in the “landscaped” labelled gardens of this period, one can observe simply extraordinary compositions made out of the juxtaposition of empty and full, out of clearings and forested areas.

Central Park, for example, is not mere greenery. It is a composition, a composition mastered to perfection. And I wonder how to develop a mastery of these empty and full spaces today. There always remains a form to give to the empty.

The landscape architects in Great Britain, in England, physically prefigure their compositions beforehand using sheets, stakes, and strings: they attempt to master the process beforehand in reality. It is terrible to believe that in planning and in perspective we can attain such a level of mastery that the space would be perfect.

For landscape compositions are also empirical works, evolving on the spot, a process during which the density of the site and its organization come to be truly understood and mastered. I believe that we should once again look at questions of spatial composition, looking at times at geometrical composition, whatever this geometry might be, while of course continuing to examine questions of texture. The combination of both I believe is the basis of a perhaps new approach in the 21st century.

SCHEMES OF VARIABLE DENSITIES

For years I have been fascinated by composing utilizing schemes of variable densities. I like putting into play these variable densities because the work of time also comes into play. These densities vary over time. If planting very compactly as in a forested area for example, the area will gradually thin out. And in choosing the best quality trees, the density too changes, the trees being thicker, higher, but less dense. Thus we can manipulate compositions using density in the present, as well as in by projecting into the future. I like stating my preference for plant nurseries to certain gardens. In a plant nursery, in a poplar grove, in an orchard, where the composition is simple, what interests me is the density: in what I see, in what I don't see, in the gradual appearance of opacity: seeing for how many tens of meters, before everything becomes opaque... Thus I like these references, again the poplar grove, the orchard, precisely because their composition is elementary, made up of a simple orthogonal geometry, while nonetheless their porosity and texture varies.

ELEMENTARY WRITING

Materials are necessarily elementary: trees, grass, water, sometimes a few mineral surfaces of stone or concrete. Using rudimentary components, and in very limited number, you can construct a classic garden, a picturesque garden, conceive of anything you desire. That is to say, with very few elements entire universes, sometimes of extremely large dimensions and of completely different natures, can be created.

I like this economy of means. On the other hand, I do not like the oftentimes perceived need of utilizing various enticing devices, believed to be the most up to date, which work rather in tarnishing and dulling the elementary character.

I like this word “elementary”. And yes, in precisely the sense of elements: grass, water, trees... and with just these, almost anything can be made. Great things can be made. It's fascinating. The rusticity of the material is extraordinary.